This article intends to review the new city of Victoria, Brasov, Romania as regarded as a Utopian City, making it the subject of Utopian Cities Programmed Societies (Heinzel & Diminescu, 2019), a research week in late June 2019. The purpose of the week was to draw inspiration through research and seminars to tackle the issues facing the city as its population constantly shrinks in number. In this article compares Victoria to contemporary new town Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire, England whose population has continually grown; and the challenges faced in constructing accessible cultural heritage in new towns.

Victoria in Brasov, Romania is a “new town” (a settlement which is planned and designed prior to construction with state funding, usually in a rural or uninhabited area. Many new towns are designed on utopian concepts of creating the perfect environment to house the perfect society). Heralded the city of pioneers, city of flowers and city of children, it was once a prosperous city providing well paid jobs. Yet, during an initial meeting with the Mayor and members of the city council the biggest issue was their ‘Shrinking city1’ populated by an ever-decreasing older population as the younger generations moved out of the city often to find work or higher education opportunities. It followed that the city council hoped for an investor to recognise the potential of the picturesque city set in the mountains as a tourist destination. This hope is built in no small part to the history of the town being founded by external investment in a munitions and later chemical factory on the edge of town. Starting off as a colony providing workers for the factory in the early 1940s the area became a city whilst Romania was under Soviet influence during the 1950s. The Mayor of Victoria stated that the city had no archive, whilst there are local maps chronically the area held at the city offices and a small museum room at the factory, it is not readily accessible without appointment.

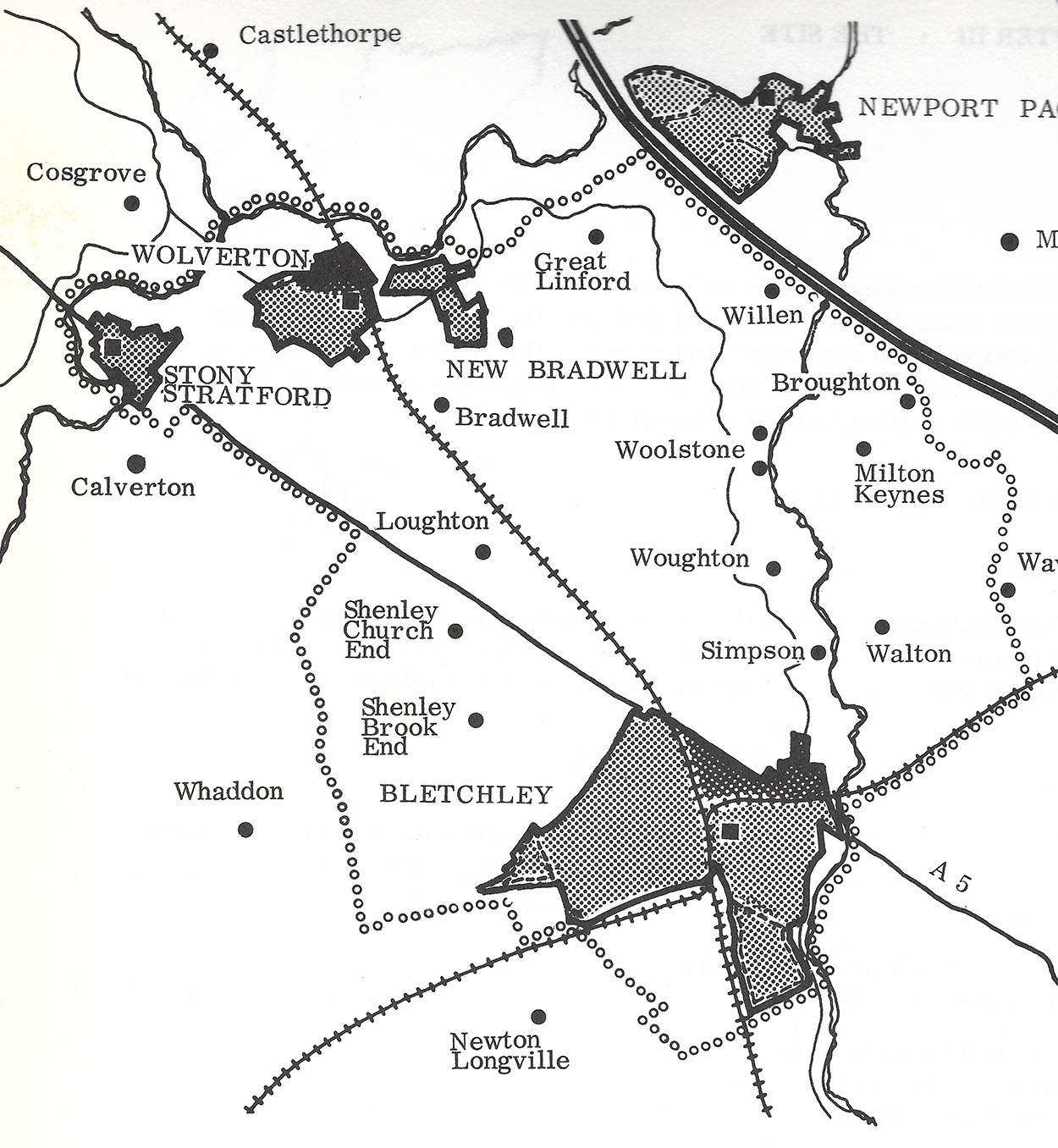

Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire, England is a new town. Heralded the city of pioneers2, city of trees but it is also derided as a soulless place of concrete and roundabouts without heritage or cultural despite having areas of history and outstanding natural beauty with many parks, woodlands and lakes. It is regarded as the most successful new town in Britain due to its rapid (and still increasing) growth, its employment levels and buoyant economy. It was designated as a ‘new city’ in 1967 under the 1946 New Towns Act. After the initial planning period by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation (Llewelyn- Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker, & Bor, 1968, 1970) construction began in 1970 and continues to present day as the ‘city’ still increases. Milton Keynes’ population rose from 44,000 in 1967 to 260,000+ in 2017. Milton Keynes includes 16 original settlements which can trace their origins back to the English Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods.

Both Victoria and Milton Keynes were designed along utopia philosophies to create a place that could maintain a happy and prosperous community but approached differently in their construction. Milton Keynes was planned to be a low-density city comprising of different areas each with its own distinct architecture and multiple industries as opposed to Victoria’s single industry which as its needs for workers has lessened has impacted the local population. Victoria is split into two main types of housing, houses and apartment blocks, with high rise buildings around the edge of the town reducing in size towards the centre where the two storey houses are situated.

As relatively new settlements both Victoria and Milton Keynes have had to manage new populations making a connection to a new area. Both have had to cultivate a heritage, in Milton Keynes this has been through the a Heritage Consortium, made up of five heritage organisations3, including the Living Archive (Living Archive, 2016) a collection of oral histories from local residents, whether original, pioneer, or more recent settlers. The oral histories include stories of everyday life to memories of extraordinary events and have inspired cultural events, plays, songs and poems about the area. Living Archive’s oral collection, as opposed to a document or object archive involves the community increasing its visibility and accessibility to the communities it serves and can exist online accessible to residents and across the globe. These stories cultivate cultural heritage by and for the residents of Milton Keynes highlighting that storytelling can be both a form of heritage, known as intangible cultural heritage (UNESCO, 2018), and a method by which to share it. Storytelling can generate understanding about an area beyond one’s own experience, and by sharing personal experiences it can create bonds within the community. Milton Keynes has used its Living Archive to engage residents, gain funding, and produce cultural events, drawing in visitors from outside the city and by making many of its resources available online raises the profile of Milton Keynes. A similar project in Victoria could produce an archive, noted by the Mayor as lacking, engage in the residents, and provide accessible information to encourage potential tourism and the hoped-for investors.

To explore this potential during the research week in Victoria residents were engaged in interviews designed to encourage the sharing of oral histories and personal narratives. Even with the limited number of residents, there were plenty of stories about the area and the individual’s experience of the area. Inspired by these stories, the landscape and Romanian folktales well known throughout the country a digital story (a two to three minutes of video combining a personal narrative with relevant images) was created (Howey, 2019) as a piece of cultural heritage and an artist’s response to exploring the themes raised during the week. Interviews and digital stories such as the ones created during the research week, along with audio recorded oral histories could be collected to start an archive which could be continually added to and reflected upon. With smart phones readily available providing access to audio and visual recording and editing apps, a resource could be generated by the residents themselves without the need for a costly investment or space to hold an archive.

By comparing Victoria and Milton Keynes we see that new towns face certain challenges surround their cultural heritage regardless of the planning, population and politics underpinning the establishment of the area. A resource of digitally archived oral histories cultivating cultural history by the residents could be a fast and low-cost method for Victoria to develop an archive which would be globally assessible. This at least addresses the cited lack of an archive but may potentially draw outside attention to the picturesque city in the mountains creating further benefits regarding tourism and investment.

NOTES:

1 A phenomenon where the population of the city quickly reduces as people migrate from the city to other areas. This issue has been experienced in many cities in Romania after the fall of Communist regime.

2 The original settlers to Milton Keynes are referred to as pioneers in response to the area having a lack of roads, infrastructure or facilities in the early part of its development, giving it a ‘wild west’-like reputation (Croft & Mynard, 1993; Finnegan, 1998, 2007; Hill, 2005; Kitchen, 2018; Turner & Jardine, 1985).

3 The five organisations are Bletchley Park, Cowper and Newton Museum, Living Archive, Milton Keynes City Discovery Centre, Milton Keynes Museum.

REFERENCES:

Agnew, J. (2011). Chapter 23: Space and Place John Agnew (University of California, Los Angeles) in J. Agnew and D. Livingstone (eds.). Handbook of Geographical Knowledge, 2011, ?? https://doi.org/10.5840/radphilrev20071022

Croft, R. A., & Mynard, D. C. (1993). The Changing Landscape of Milton Keynes. Aylesbury: Longdunn.

Finnegan, R. (1998). Tales of the City: A Study of Narrative and Urban Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Finnegan, R. (2007). The Hidden Musicians: Music-Making in an English Town (2nd ed.). Wesleyan University Press.

Heinzel, T., & Diminescu, D. (2019). Utopian Cities Programmed Societies. Utopian Cities Programmed Societies. Victoria, Brasov, Romania: 2580 Association. Hill, M. (2005). Milton Keynes: A history & celebration. Sailsbury: The Francis Frith Collection.

Howey, T. (2019). Sweet Victoria – Draga Victoria. Retrieved October 23, 2019, from YouTube website: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=oVu50q3CQKs&t=5s

Kitchen, R. (2018). Make No little Plans. England: Living Archive.

Kolodziejski, A. L. (2014). Connecting People and Place : Sense of Place and Local Action.

Living Archive. (2016). Living Archive | A living history of Milton Keynes. Retrieved July 13, 2019, from Living Archive website: https://www.livingarchive.org.uk/

Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier- Walker, & Bor. (1968). Milton Keynes: Interim Report. London.

Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier- Walker, & Bor. (1970). The Plan for Milton Keynes. London.

Milton Keynes Development Corporation. (1970). The Plan for Milton Keynes Volume Two. London.

Turner, J., & Jardine, B. (1985). Pioneer Tales. Stantonbury: People’s Press.

UNESCO. (2018). Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paris, France.

———————————————————————

NOTES PHOTOS:

Photo Dance – A cultural heritage event ‘day of dance’ in Stony Stratford, Milton Keynes. Credits: Terrie Howney.

Photo Pyramid – A piece of modern architecture in the centre of Milton Keynes known as ‘the point’ because of its pyramid structure. It is at the centre of fierce cultural heritage debate as the town councillors plan to tear it down and many residents protest to keep it.

Map – The layout of Milton Keynes including the original settlements, this is from the Milton Keynes Development Corporation Plan, as referenced in the article.

This article intends to review the new city of Victoria, Brasov, Romania as regarded as a Utopian City, making it the subject of Utopian Cities Programmed Societies (Heinzel & Diminescu, 2019), a research week in late June 2019. The purpose of the week was to draw inspiration through research and seminars to tackle the issues facing the city as its population constantly shrinks in number. In this article compares Victoria to contemporary new town Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire, England whose population has continually grown; and the challenges faced in constructing accessible cultural heritage in new towns.

Victoria in Brasov, Romania is a “new town” (a settlement which is planned and designed prior to construction with state funding, usually in a rural or uninhabited area. Many new towns are designed on utopian concepts of creating the perfect environment to house the perfect society). Heralded the city of pioneers, city of flowers and city of children, it was once a prosperous city providing well paid jobs. Yet, during an initial meeting with the Mayor and members of the city council the biggest issue was their ‘Shrinking city1’ populated by an ever-decreasing older population as the younger generations moved out of the city often to find work or higher education opportunities. It followed that the city council hoped for an investor to recognise the potential of the picturesque city set in the mountains as a tourist destination. This hope is built in no small part to the history of the town being founded by external investment in a munitions and later chemical factory on the edge of town. Starting off as a colony providing workers for the factory in the early 1940s the area became a city whilst Romania was under Soviet influence during the 1950s. The Mayor of Victoria stated that the city had no archive, whilst there are local maps chronically the area held at the city offices and a small museum room at the factory, it is not readily accessible without appointment.

Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire, England is a new town. Heralded the city of pioneers2, city of trees but it is also derided as a soulless place of concrete and roundabouts without heritage or cultural despite having areas of history and outstanding natural beauty with many parks, woodlands and lakes. It is regarded as the most successful new town in Britain due to its rapid (and still increasing) growth, its employment levels and buoyant economy. It was designated as a ‘new city’ in 1967 under the 1946 New Towns Act. After the initial planning period by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation (Llewelyn- Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker, & Bor, 1968, 1970) construction began in 1970 and continues to present day as the ‘city’ still increases. Milton Keynes’ population rose from 44,000 in 1967 to 260,000+ in 2017. Milton Keynes includes 16 original settlements which can trace their origins back to the English Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods.

Both Victoria and Milton Keynes were designed along utopia philosophies to create a place that could maintain a happy and prosperous community but approached differently in their construction. Milton Keynes was planned to be a low-density city comprising of different areas each with its own distinct architecture and multiple industries as opposed to Victoria’s single industry which as its needs for workers has lessened has impacted the local population. Victoria is split into two main types of housing, houses and apartment blocks, with high rise buildings around the edge of the town reducing in size towards the centre where the two storey houses are situated.

As relatively new settlements both Victoria and Milton Keynes have had to manage new populations making a connection to a new area. Both have had to cultivate a heritage, in Milton Keynes this has been through the a Heritage Consortium, made up of five heritage organisations3, including the Living Archive (Living Archive, 2016) a collection of oral histories from local residents, whether original, pioneer, or more recent settlers. The oral histories include stories of everyday life to memories of extraordinary events and have inspired cultural events, plays, songs and poems about the area. Living Archive’s oral collection, as opposed to a document or object archive involves the community increasing its visibility and accessibility to the communities it serves and can exist online accessible to residents and across the globe. These stories cultivate cultural heritage by and for the residents of Milton Keynes highlighting that storytelling can be both a form of heritage, known as intangible cultural heritage (UNESCO, 2018), and a method by which to share it. Storytelling can generate understanding about an area beyond one’s own experience, and by sharing personal experiences it can create bonds within the community. Milton Keynes has used its Living Archive to engage residents, gain funding, and produce cultural events, drawing in visitors from outside the city and by making many of its resources available online raises the profile of Milton Keynes. A similar project in Victoria could produce an archive, noted by the Mayor as lacking, engage in the residents, and provide accessible information to encourage potential tourism and the hoped-for investors.

To explore this potential during the research week in Victoria residents were engaged in interviews designed to encourage the sharing of oral histories and personal narratives. Even with the limited number of residents, there were plenty of stories about the area and the individual’s experience of the area. Inspired by these stories, the landscape and Romanian folktales well known throughout the country a digital story (a two to three minutes of video combining a personal narrative with relevant images) was created (Howey, 2019) as a piece of cultural heritage and an artist’s response to exploring the themes raised during the week. Interviews and digital stories such as the ones created during the research week, along with audio recorded oral histories could be collected to start an archive which could be continually added to and reflected upon. With smart phones readily available providing access to audio and visual recording and editing apps, a resource could be generated by the residents themselves without the need for a costly investment or space to hold an archive.

By comparing Victoria and Milton Keynes we see that new towns face certain challenges surround their cultural heritage regardless of the planning, population and politics underpinning the establishment of the area. A resource of digitally archived oral histories cultivating cultural history by the residents could be a fast and low-cost method for Victoria to develop an archive which would be globally assessible. This at least addresses the cited lack of an archive but may potentially draw outside attention to the picturesque city in the mountains creating further benefits regarding tourism and investment.

NOTES:

1 A phenomenon where the population of the city quickly reduces as people migrate from the city to other areas. This issue has been experienced in many cities in Romania after the fall of Communist regime.

2 The original settlers to Milton Keynes are referred to as pioneers in response to the area having a lack of roads, infrastructure or facilities in the early part of its development, giving it a ‘wild west’-like reputation (Croft & Mynard, 1993; Finnegan, 1998, 2007; Hill, 2005; Kitchen, 2018; Turner & Jardine, 1985).

3 The five organisations are Bletchley Park, Cowper and Newton Museum, Living Archive, Milton Keynes City Discovery Centre, Milton Keynes Museum.

REFERENCES:

Agnew, J. (2011). Chapter 23: Space and Place John Agnew (University of California, Los Angeles) in J. Agnew and D. Livingstone (eds.). Handbook of Geographical Knowledge, 2011, ?? https://doi.org/10.5840/radphilrev20071022

Croft, R. A., & Mynard, D. C. (1993). The Changing Landscape of Milton Keynes. Aylesbury: Longdunn.

Finnegan, R. (1998). Tales of the City: A Study of Narrative and Urban Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Finnegan, R. (2007). The Hidden Musicians: Music-Making in an English Town (2nd ed.). Wesleyan University Press.

Heinzel, T., & Diminescu, D. (2019). Utopian Cities Programmed Societies. Utopian Cities Programmed Societies. Victoria, Brasov, Romania: 2580 Association. Hill, M. (2005). Milton Keynes: A history & celebration. Sailsbury: The Francis Frith Collection.

Howey, T. (2019). Sweet Victoria – Draga Victoria. Retrieved October 23, 2019, from YouTube website: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=oVu50q3CQKs&t=5s

Kitchen, R. (2018). Make No little Plans. England: Living Archive.

Kolodziejski, A. L. (2014). Connecting People and Place : Sense of Place and Local Action.

Living Archive. (2016). Living Archive | A living history of Milton Keynes. Retrieved July 13, 2019, from Living Archive website: https://www.livingarchive.org.uk/

Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier- Walker, & Bor. (1968). Milton Keynes: Interim Report. London.

Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier- Walker, & Bor. (1970). The Plan for Milton Keynes. London.

Milton Keynes Development Corporation. (1970). The Plan for Milton Keynes Volume Two. London.

Turner, J., & Jardine, B. (1985). Pioneer Tales. Stantonbury: People’s Press.

UNESCO. (2018). Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paris, France.